“Identity is like a mousetrap in which more and more mice have to share the original bait, and which, on closer inspection, may have been empty for centuries.”

– Rem Koolhaas, The Generic City

Museum Archives

The Gyeongju National Museum has functioned as an archive of Korean modern and contemporary museum architecture over the past 50 years, opening major permanent exhibition halls including Silla History Gallery (Hee-tae Lee, 1975), Wolji Gallery (Swoo-geun Kim, 1982), Silla Art Gallery (2002), and Treasury of the Silla Millennium (2019). Located in the Historical and Cultural District where each building must be constructed according to the shape of a hanok, the architecture of the National Museum has been a venue for experimentation and debate on the representation of traditionality and Korean uniqueness. The West Annex Hall, built in 1979 as a public office facility, was remodeled as a storage room in 2008, undergoing various changes such as cement plastering for the exterior brick walls and integrating the space by removing the interior masonry walls. As part of the mid- to long-term development plan, the National Museum decided to remodel the now 40-year-old hall into an archive of Silla historical documents.

Old Building

The West Annex Hall is a building that exemplifies the traditionality of the Korean architecture sphere of the 1970s in its representation of the wooden structure of a Silla hanok in reinforced concrete. The floor plan has the form of a 15-square house with five rows at the front and three rows on the sides, and the eaves protruding from the front center row highlight the entrance. Unlike the floor plan for a traditional wooden structure, the side center row is designed to be a narrow module of 2.6m. This is because a modern corridor was arranged at the center row for functional reasons. In this way, the spatial form was determined by the intended use, rather than the structural characteristics of the building materials. In addition to poor construction quality, the process of converting the shape of the wooden structure to a concrete one has exhibited many limitations in terms of the overall perfection of the structures, including oversimplified expressions and awkward details. Due to budget limitations, we plan to proceed with the design focusing on the interior space requiring the practical functions of the library while satisfying the minimum requirements for the exterior of the building.

From the Phantom of Traditionality to Novel Historicity

The morphological aesthetics of the existing West Annex Hall leads to an architectural conundrum that has been incessantly recurrent in the field over its long history: how to integrate the past, present and future in context. What meaning would the traditional architecture of Silla a thousand years ago have had in the South Korea of the 1970s? How was the architecture of the 1970s appreciated in the South Korea of the 2000s, which attempted to reproduce the traditionality of Silla? What is the relationship between the building’s new function and its required ‘traditional’ form under circumstances where its use has changed several times over the decades? As Rem Koolhaas indicated, architecture aiming at traditionality becomes a tautological, ‘empty’ construction when traditional identity is solely defined as past-oriented. Without the pursuit of coherence, prioritizing the future-oriented values over the past and present, it will become a construction of empty echoes. Historical cultural heritage can deliver a unique and sustainable value only when it is reinterpreted with a sense of ‘presentness’ and related to the future via the concept of a historical continuum.

A Problematic Return: from Stereotomics to Tectonics

The West Annex Hall attempted to reproduce the traditionality of Silla by fabricating the traditional wooden hanok structure with reinforced concrete, stacking masonry walls between the columns, and adding cement plastering. Built with a low budget in a corner of a local museum in the 1970s, the expression and detail of the materials are crude to the point of being considered postmodern kitsch. This building raises an interesting conceptual problem regarding the relationship between construction technology and representation in architecture. Given that the properties and construction technologies of concrete are different from those of wood, what is the significance of expressing traditionality by borrowing the outward appearance alone? Back in 1828, German architect Heinrich Hübsch published a critique on this issue, sparking a fierce debate in the architectural circle at that time. The classical style of Western architecture is, as a matter of fact, one in which the joint details derived from wooden structures had been transferred to stone structures, leaving traces of its previous form. In this respect, Hübsch was critical of the neoclassical methodology that borrowed a style from the past, rooted in different material properties under the situation where new materials and technologies were being applied to a new era.

Gottfried Semper classified architecture into tectonics and stereotomics, depending on the means of construction. According to this classification, the wooden structure of hanok, in which pieces of different lengths are combined to create a frame surrounding the space, is categorized as tectonic; while stone or concrete structures can be classed as stereotomic, in which weighty masses are stacked or hardened to form a space. Despite Hübsch’s criticism of neoclassicalism, inconsistent or vague classifications of construction technology and representations have been utilized throughout the history of mankind. The Temple of Athena at Paestum maintains the two modes where columns and beams meet: the junction of beams is performed through the wooden tectonic mode, while the columns were fabricated with stones in the stereotomic mode. The technology for the Great Temple at Petra, Jordan is classified as stereotomic because this temple was constructed by knobbing and cutting stones, despite the form being seemingly realized by a tectonic process. These two temples serve as cases leaving a room for pluralistic interpretations over whether an artform is defined by the properties of the material (materiality), or the creative drive (kunstwollen). This provides a source of inspiration for creative counter-intuition about timeless styles.

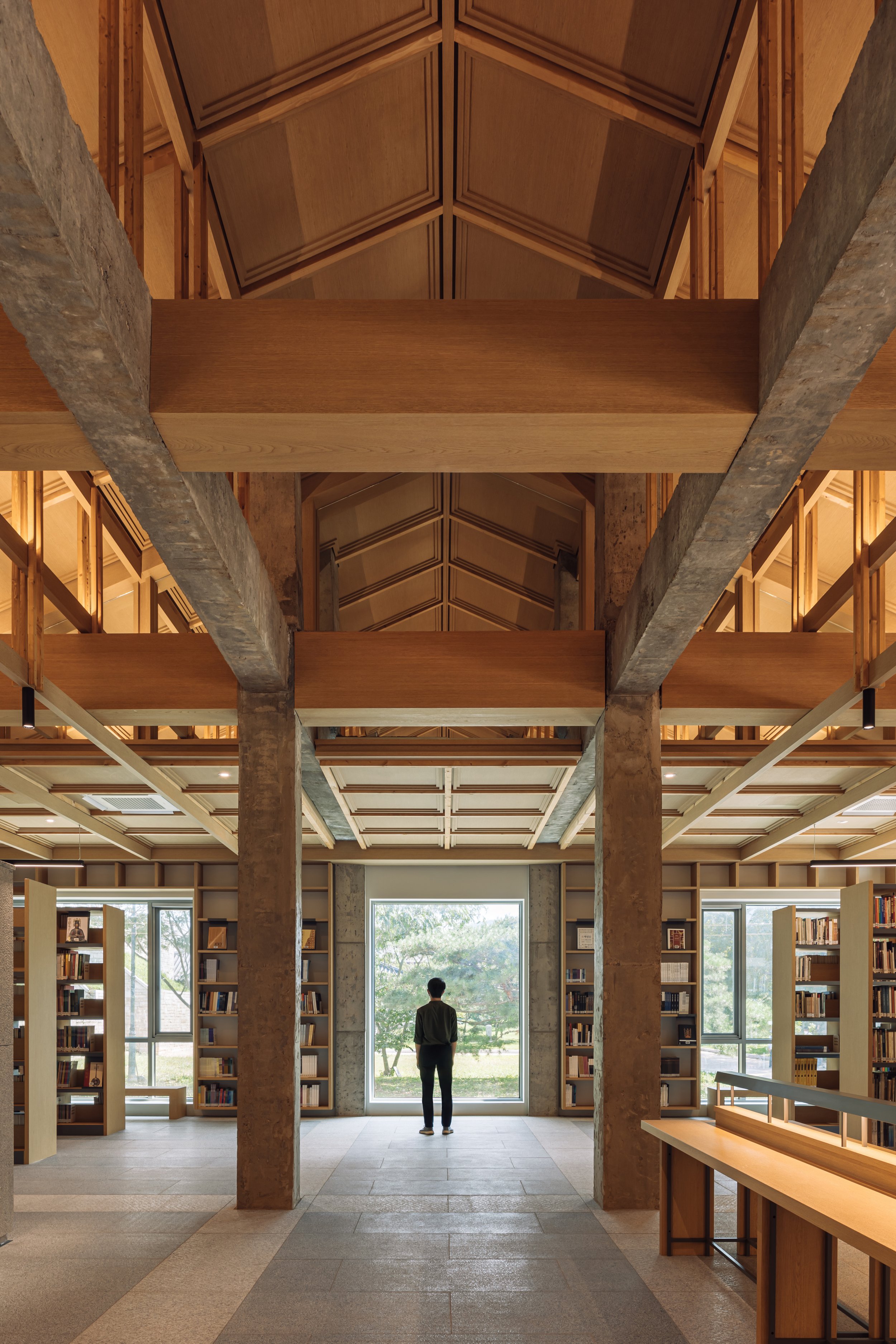

The existing West Annex Hall had been constructed by implementing the appearance of the tectonic form of the traditional wooden structure through the construction technology of stereotomics. A purely stereotomic concrete structure remains in the interior of this building after the removal of a partition wall and a ceiling for remodeling. Following Hübsch, what kind of space could be constructed in the interior under circumstances where budget limitations require the project to focus mainly on the interior? Moreover, what relationship would the interior space have with the existing exterior of the building? Taking over the incomplete work based on the stereotomic implementation of tectonic traditionality in the 1970s when South Korea had been a poor country, we aim to realize a wooden tectonic structure that will be extended from the stereotomic concrete structure to the interior space. This work is a transition to a novel historicity extending the concept of traditionality beyond mimesis of past heritage into the emotional effects (affect) of the material and joint.

The Fantasy of the Architectural Bookscape

The library is the architectural fantasy of the zeitgeist about the space of sacred knowledge. The architectural representations of library bookscapes have varied in each era, including the centripetal bookshelves of Stockholm Public Library (Gunnar Asplund, 1928), bookshelves surrounding nine-square voids in Public Library Stuttgart (Eun-young Lee, 2011), the diagonally open reading space of the Bibliotheca Alexandrina (Snøhetta, 2011), and the successive ramps of Jussieu Library (OMA, 1992). However, these attempts, by their nature, have not significantly deviated from the neoclassical Bibliothèque du Roi planning (1785) of Étienne-Louis Boullée. The library is a fantasy space where divine light illuminates from the sky, and the field of knowledge surrounded by books unceasingly expands.

The Haeinsa Temple Janggyeong Panjeon is a building preserving Tripitaka Koreana (81,258 wooden printing blocks) from the Goryo period. It is the oldest building in Haeinsa Temple. Panga (Tripitaka storage) is placed along the purlin direction inside Sudara-jang and Beopbo-jeon, housing printing blocks which resemble the bookshelves of a library. Although the wooden structure of Panga is not directly connected to that of Panjeon architecture, this juxtaposition of timber structures creates a spatial aesthetic fantasy integrating architecture and Panga due to their resemblance in material and form. In a situation where existing library constructions or historical materials from the Silla period are absent, it is impossible to reproduce the traditions of Silla through historical investigation. Alternatively, we aimed to implement a new historical bookscape that reinterprets the spatial aesthetics of the Haeinsa Janggyeong Panjeon, the oldest of the times, from the present viewpoint.

The Silla Millennium Archive is a project that has a problem of asymmetry in the interior space because only 12-square space among the existing West Annex Hall are available for library use: four out of five front rows, excluding one row in the north, as well as three rows on the sides. In addition, the requirements of the program, including a reading space, a librarian space, and a book curation space are realistic factors that compromise the order of the spatial form. How can we resolve the contradiction between architectural ideals of symmetry and balance, and the asymmetric interior space? Mirrors reflect the entity of reality, create a virtual illusion, and expand the world of senses beyond the limits of physical space. The symmetrical encounter of the two worlds at the interface of mirror surfaces has played a role in reinterpreting the meaning of being and delivering hidden symbols in classical and contemporary arts. In the Silla Millennium Archive, the mirror installed in the pediment reflects the shape of the asymmetric space, creating the illusion of symmetrical order and extending the space of knowledge beyond physical boundaries. The mirror is a spatial metaphor for a thousand-year-old historical document archive, as well as an architectural fantasy about the endlessly extending bookscape.

박물관 아카이브

국립경주박물관은 지난 50여년 동안 신라역사관(이희태, 1975)을 시작으로 월지관(김수근, 1982), 신라미술관(2002) 등의 주요 상설전시관과 특별전시관(1982), 그리고 대규모 문화재 보관 시설인 신라천년보고(2019)를 갖추며 한국 근현대 박물관 건축의 아카이브로 기능해왔다. 맥락적으로 한옥의 형태를 따라야 하는 역사문화미관지구에 속해 있어, 1975년에 개관한 신라역사관에서부터 1982년의 월지관, 2019년의 신라천년보고에 이르기까지 국립경주박물관의 건축은 전통성과 한국성의 표상에 대한 실험과 논란의 장이 되어왔다. 1979년 업무시설로 지어진 서별관(건축가 미상, 1979)은 2008년 수장고로 개보수되면서 외관의 벽돌벽에 시멘트 미장을 하고 내부 조적벽체를 터서 공간을 통합하는 등의 크고 작은 변화들이 있었다. 국립경주박물관은 중장기 발전계획의 일환으로 40년이 넘은 서별관 건물을 신라역사문헌 아카이브로 리모델링하기로 결정했다.

오래된 건물

서별관은 신라 한옥의 목구조를 철근콘크리트로 재현하고자 한 70년대 한국건축계의 전통성에 대한 고민이 담겨있는 건축물이다. 평면구성은 정면 5칸, 측면 3칸의 15칸집의 형식을 갖추고 있고 정면 가운데 칸에서 돌출된 처마가 입구성을 강조하고 있는 모습이다. 전통 목구조의 평면 형식과는 달리 측면의 가운데 칸이 2.6m의 좁은 모듈로 되어 있는데, 이는 기능적인 이유로 가운데 칸에 근대식 복도가 배치되면서 공간의 형식이 건축 부재의 구조적 특성이 아닌 내부의 프로그램에서 기인했기 때문이다. 기와지붕에 신라시대의 치미를 갖추는 등 역사성에 대한 고민이 담겨있지만 목구조의 형태를 콘크리트로 변환하는 과정에서 지나치게 단순화된 부재의 표현과 어색한 디테일, 조악한 시공 품질 등 전반적인 건축의 완성도 측면에서는 많은 아쉬움이 있는 건물이다. 예산의 한계로 인해 외관은 최소한으로 정리하고 도서관의 실질적인 기능을 갖추어야 하는 내부 공간을 중심으로 설계를 진행하기로 한다.

전통성의 환영에서 새로운 역사성으로

기존 서별관의 형태미학은 오랜 역사를 거치며 건축에서 수없이 되풀이 되어온 건축적 난제들을 다시 불러일으킨다. 1970년대 한국에서, 천년 전에 존재했던 신라의 전통 건축은 어떤 의미를 가지는가? 혹은, 2020년대 한국에서, 신라의 전통성을 재현하려고 한 1970년대 건축물의 가치는 어떻게 판단할 것인가? 지은지 40년이 넘은 건축물의 용도가 세번 째 바뀌는 상황에서 새로운 프로그램과 기존 건축물의 전통적(?) 형태는 어떤 관계를 맺을 것인가? 쿨하스(Rem Koolhaas)가 지적한 바와 같이, 전통성이라는 정체성을 과거 지향적으로만 정의할 때 전통성의 건축은 공허한 동어반복의 건축이 된다. 또한, 미래 지향성의 가치만을 우위에 두고 과거와 현재의 배제를 통한 통일성을 추구한다면 그 또한 공허한 메아리의 건축이 될 것이다. 과거의 문화유산을 현재성으로 재해석하고 연속되는 역사성의 개념으로 미래와 관계 맺을 때 비로소 지속가능한 고유의 가치를 만들어낼 수 있을 것이다.

스테레오토믹에서 텍토닉으로의 귀환

서별관은 한옥의 목구조 형태를 철근콘크리트 구조로 만든 후 기둥과 기둥 사이에 조적벽을 쌓고 시멘트 미장을 더해 신라의 전통성을 재현하려고 한 건물이다. 70년대 지방 박물관 한쪽 귀퉁이에 저예산으로 지어진 만큼 부재의 표현과 디테일이 조악해 어찌보면 포스트모던의 키치(kitsch) 버전스럽기도 하지만, 건축에서의 구축기술과 표상의 관계에 대한 흥미로운 개념적 문제를 내재한 건물이다. 콘크리트의 물성과 구축기술은 목재의 그것과 다름에도 불구하고 겉으로 드러나는 모습만 차용해 전통성을 표상하는 것은 무슨 의미가 있는가? 시대를 거슬러 약 200년 전인 1828년 독일 건축가 휩쉬(Heinrich Hübsch)가 발표한 논문 <In What Style Should We Build?> 역시 비슷한 문제의식을 가지고 있었고 당시 건축계에서 큰 논쟁을 불러일으켰다. 서양건축의 고전 양식은 사실 목구조에서 기인한 부재의 접합 디테일이 석조로 전환되면서도 그 형태의 흔적이 남아서 양식화된 것인데, 휩쉬는 새로운 시대에 새로운 재료와 기술로 건축을 하는 상황에서 다른 물성에서 기인한 과거의 양식을 차용하는 신고전주의적 방법론에 대해 비판적 입장이었다.

젬퍼(Gottfried Semper)는 건축을 구축 방식에 따라 텍토닉(tectonics)과 스테레오토믹(stereotomics)으로 분류했다. 길이가 여러 가지인 부재를 결합해서 공간을 둘러싸는 틀을 만드는 한옥의 목구조는 텍토닉으로, 중량감 있는 덩어리를 쌓거나 굳혀 공간을 형성하는 석조나 콘크리트는 스테레오토믹으로 분류할 수 있겠다. 휩쉬의 신고전주의에 대한 비판에도 불구하고 역사적으로 구축기술과 표상이 일치하지 않거나 모호한 선례들은 늘 인류 역사와 함께 해 왔다. 파에스툼(Paestum)의 아테나 신전은 기둥과 보가 만나는 형식, 그리고 보의 접합은 목조 텍토닉의 형식을 유지하고 있지만 기둥 자체는 일정한 석재 덩어리를 쌓아서 만든 스테레오토믹의 형식을 취하고 있다. 요르단의 페트라(Petra) 신전은 암석을 깎고 잘라내어 만든 것으로 구축 기술은 스테레오토믹으로 분류되지만 결과적으로는 텍토닉에 의해 구현된 듯한 형태를 얻어냈다. 파에스툼과 페트라는 예술의 형태가 물질의 물성(materiality)에서 나오는 것이냐, 예술의지(kunstwollen)에서 나오는 것이냐에 대한 다원적인 해석의 여지를 주는 선례이며, 시대를 초월해 양식에 대한 창의적인 역발상을 가능하게 하는 영감의 원천이 된다.

기존 서별관은 외관에서 전통 목구조의 텍토닉 형태를 스테레오토믹의 구축 기술로 구현한 것이다. 리모델링을 위해 칸막이벽과 천장을 철거한 후의 내부는 순수하게 스테레오토믹의 콘크리트 구조만 남아있다. 예산의 한계로 프로젝트의 범위가 실내에 집중된 상황에서 내부에 어떤 건축 공간을 만들어낼 것인가?(In What Style Should We Build?) 그리고 내부 공간은 건물의 기존 외관과 어떤 관계를 맺을 것인가? 한국이 아직 가난했던 70년대, 예산과 기술의 한계로 스테레오토믹으로 구현하려고 했던 텍토닉의 전통성, 그 미완의 작업을 이어받아 스테레오토믹 콘크리트 구조에서 내부로 확장되는 목구조 텍토닉을 구현하려고 한다. 이는 과거유산의 형태모방(mimesis)에만 국한시켰던 전통성의 개념을, 공간을 정의하는 재료의 물성과 조인트(joint)의 정서적 효과(affect)로 확장시켜 재해석하는 새로운 역사성(novel historicity)으로의 전환이다.

책풍경의 판타지

도서관은 신성한 지식의 공간에 대한 시대정신의 건축적 판타지이다. 스톡홀름 공공도서관(Gunnar Asplund, 1928)의 구심형 서가, 슈투트가르트 시립도서관(이은영, 2011)의 구정방(nine-square) 보이드를 둘러싸는 서가, 알렉산드리아 도서관(Snøhetta, 2011)의 사선으로 오픈된 열람 공간, 주시우 도서관(OMA, 1992)의 연속되는 경사로 등 도서관 책풍경(bookscape)에 대한 각 시대의 건축적 재현은 다양하게 나타나지만 그 본질은 신고전주의 건축가 불레(Étienne-Louis Boullée)의 도서관 계획(Bibliothèque du Roi, 1785)과 그다지 다르지 않다. 도서관은 하늘에서 신성한 빛이 떨어지고 책으로 둘러싸인 지식의 장이 끝없이 확장하는 판타지의 공간이다.

해인사 장경판전은 고려시대의 8만여장의 대장경판을 보관하고 있는 건물로, 해인사의 현존 건물 중 가장 오래된 건물이다. 판전인 수다라장과 법보전 내부에는 경판을 꽂아둔 판가가 도리방향으로 길게 놓여 있는데 도서관의 서가를 닮았다. 판가의 목구조는 판전 건축의 목구조에 직접적으로 결구되어 있지는 않지만 재료와 형식이 닮아 건축과 판가가 하나로 통합된 공간미학적 판타지를 만들어낸다. 현존하는 신라 시대의 도서관 건축이나 사료가 없는 상황에서 고증을 통해 신라의 전통성을 재현하는 것은 불가능하다. 대신, 시대적으로 가장 오래된 장경판전의 공간미학을 현재의 시점으로 재해석한 새로운 역사성의 책풍경을 구현하고자 했다.

신라천년서고는 기존 서별관의 정면 5칸 중 북측의 1칸을 제외한 4칸과 측면 3칸의 12칸만 도서관으로 쓸 수 있어 내부공간의 비대칭 문제를 해결해야 하는 프로젝트이다. 또한, 열람 공간, 사서 공간, 북큐레이션 공간 등 프로그램의 요구사항 역시 공간 형식의 질서를 타협시키는 현실적인 요인들이다. 대칭과 균형의 건축 형식과 비대칭적인 내부공간의 모순을 어떻게 해결할 수 있을까? 거울은 현실의 실재를 비추며 가상의 환영을 만들어내고 실제 공간의 한계를 넘어 감각의 세계를 확장시킨다. 거울면의 경계에서 만나는 두 세계의 대칭적 조우는 고전과 현대예술에서 존재의 의미를 재해석하고 숨겨진 상징을 전달하는 역할을 해왔다. 신라천년서고에서 로비 상부 박공(pediment) 영역에 설치된 거울은 비대칭 공간의 형상을 반사해 대칭적 질서의 환영을 만들어내고 지식의 공간을 물리적인 경계 너머로 확장시킨다. 거울은 천년의 역사문헌 아카이브에 대한 공간적 은유이며 끝없이 뻗어나가는 책풍경에 대한 건축적 판타지이다.